The evening amusements of the English Monarch were opulent spectacles. At this time of day in particular, the beautiful and the rich indulged their passions. At the theatre, the opera, great balls or courtly gatherings, one could see the cultural bloom of the restored monarchy, which was inspired by numerous foreign examples. Take a seat next to Charles II in the royal box and get to know the debaucherous pleasures of the king!

One of the most exclusive evening events at the court of Charles II was the so-called ‘drawing rooms’. They took place in the private chambers of the queen. Henrietta Maria brought these gatherings to England based on the French tradition of the salon. She was the mother of Charles II and was descended from the French royal house. Under the direction of Charles’ wife, Catherine of Braganza, these frequent meetings became very popular. Thus, English courtiers as well as international guests came together at the queen’s ‘drawing rooms’ to pay their respects. They gathered to discuss art, music, current events, and politics, as well as to drink and play cards. It was a good chance flirt in a less formal environment, to see and be seen, and to show off the latest fashions and trends. Furthermore, it was a good opportunity to meet the king. Because his wife hosted these evenings, he was not responsible for the amusement of the guests. In this way he could meet important courtiers or diplomates and royal visitors from all over the world privately.

– M. Ren.

This aquarell conveys an impression of how the ‘drawing rooms’ may have looked. The name of the event comes from their venue, the queen’s drawing room; every royal apartment included such a room and was originally established as a space for privacy and retreat (this is the origin of the name ‘withdrawing room’). Charles Wild’s picture shows the queen’s drawing room in Windsor Castle, in which Catherine of Braganza often held court, especially in the summer months. Between 1676 and 1678 Antonio Verrio worked on a ceiling painting for the room. This picture shows the Olympian gods and thereby reflects the courtly society gathered in the ‘drawing room’. From this room one could gain access to the private art gallery, the queen’s bedchamber and also the ‘eating room’, in which dinners were sometimes held.

– M. Ren.

‘All the World’s a Stage’: Courtly Passion for Theatre

Margaret Hughes is considered the first professional actress on an English stage. The mezzotint by an unknown artist reproduces a painting made of Hughes by the court painter Peter Lely in 1677. The young lady is portrayed quite in keeping with the taste of the time in a casual, wide-cut dress. Her gaze seems to fix the viewer and invite him to come closer to her; she plays with her long hair, producing a flirtatious, erotic effect.

The ‘classical’ theater world was a male domain until the early seventeenth century. The sometimes frivolous theatrical life was considered disreputable and unseemly for women. It was not until the Restoration that cultural life was again able to develop under Charles II from 1660. Hughes was highly esteemed for her talent by numerous patrons such as Samuel Pepys. Her long-time lover Prince Ruprecht of the Rhine, Duke of Cumberland was also a great supporter of her talent. This led to her being allowed to star in plays by Settle and Dryden at the Duke’s Theatre.

– R. Re.

A Stage for the King’s Brother: The Duke’s Theatre

The opera The Empress of Morocco was a co-production of Elkanah Settle (libretto) and Matthew Locke (music). The stage design depicted in the libretto provides a view of the stage of the Duke’s Theatre in Dorset Gardens, London, which opened in 1671. The name of the theater referred to the fact that it was financed by the Duke of York, the brother of King Charles II. Accordingly, the royal coat of arms, held by two putti, is displayed above the stage. In the stage itself, the backdrop of a spacious hall-like dungeon can be discerned. Two individual figures stand on the stage facing the auditorium. The one on the right can be identified as the figure of Muly Labas, played by the then famous singer Henry Harris.

Operas were still a very new art form in England. The first English opera is considered to be The Siege of Rhodes which premiered in 1656 in a production by William Davenant, in which Henry Harris also participated. Davenant’s libretto was set to music by several composers, including Matthew Locke.

– R. Re.

This portrait shows the English Baroque composer Matthew Locke (1621–1677), who participated in the first English opera productions. The painting is characterized by dark colors such as black, brown and gray. Only the composer’s head stands out brightly. A voluminous black coat surrounds his upper body, which seems to blur with the dark background. His dreamy gaze into the distance seems searching and enraptured.

Locke’s musical career began as a choirboy under the direction of the composer Edward Gibbons. Around 1648, Locke moved to the United Netherlands, more precisely to Charles II’s court in exile at The Hague. Under the rule of Oliver Cromwell, British cultural life stagnated; for example, the performance of plays was forbidden. With the return of the Stuarts and the restoration of the monarchy, the situation changed radically. Theaters were reopened, and Locke was given a position as ‘Composer in the Private Music’ at the court of Charles II. Numerous other musical dramas followed during this period, such as The Empress of Morocco in 1673. Locke’s pupils included Henry Purcell, who took over his post as court composer for the royal string orchestra after Locke’s death.

– R. Re.

The violin is THE instrument of the baroque. Countless baroque chaconnes, bourées, suites and other pieces were composed for this instrument. The violin shown here was made around 1685. The top and sides are made of pine, the body of sycamore maple. Spiral ornaments and the royal coat of arms decorate the instrument. The cross at the top of the fingerboard has the shape of a woman’s head. The instrument is unsigned, but has been attributed to luthier Ralph Agutter, who worked at London Bridge between 1648 and 1680. The lavish decoration and the Stuart coat of arms probably indicate that the instrument belonged to the household of Charles II or James II.

It is known that Charles II particularly appreciated the ‘lively’ sounds of the violin. Until 1663, the choirmaster Thomas Baltzar (called ‘Lubicer’), who was born in Lübeck, was in his service. Baltzar enchanted the British:

“This night I was invited by Mr. Rog: L’Estrange to heare the incomperable Lubicer on the Violin, his variety upon a few notes & plaine ground with that wonderfull dexterity, as was admirable, & though a very young man, yet so perfect & skillful as there was nothing so crosse & perplext, which being by our Artists, brought to him, which he did not at first sight, with ravishing sweetenesse & improvements, play off, to the astonishment of our best Masters: In Summ, he plaid on that single Instrument a full Consort, so as the rest, flung-downe their Instruments, as acknowledging a victor.”

(John Evelyn, Diary, 4 March 1656)

After Baltzar’s death, the violinist and composer John Banister succeeded him in 1663. His virtuosity on the violin was legendary – and his quality standards no less so. According to a receipt from Charles II’s Lord Chamberlain, Banister paid forty pounds for two violins from Cremona. This corresponded to twice the average annual income of a court musician.

– R. Re.

In this painting by Hieronymus Janssens, we see Charles II joining a prom in The Hague in the last year of his exile. He and his sister Mary are dancing a French dance named ‘Courante’ in front of a large audience in a festive hall. They wear the typical French-inspired fashions, which were common for grand celebrations. In the course of the Restauration and the king’s return to London, he brought French fashion, ceremonial festivities and dances to England.

Dance as an instrument for representation and an aristocratic art spread through all the European courts in the Baroque period. It was a part of every courtly event, including banquettes, baptisms, weddings and plays. Dance practise was part of the daily life of a courtier, as well as lessons in manners or music. Charm, graceful movements, and a noble bearing were just as necessary in the ballroom as in the daily life of the king and his court.

It is important to note that the role of women in sixteenth and seventeenth-century couples’ dances was different from that of today, when the woman typically follows the man’s lead. Previously, the dance partners were quite equal, and women sometimes even invited men to dance.

– M. Ren.

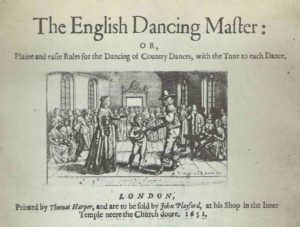

Fundamental for our knowledge of British dancing-culture is The English Dancing Master, a collection of English dances and compositions in written form. The publisher John Playford (1623–1687) was neither an author, nor a composer, nor a dancer. Out of personal interest and with the help of some friends who were musicians, composers and publishers, he collected a number of compositions and corresponding dances. He soon realized there was a demand for a written summary to accompany this collection. He therefore printed the first edition of The English Dancing Master in 1651. This version comprised 105 dances, including older ones from the time of Elizabeth I, as well as new ones, such as modern ‘country dances’. ‘Country’ here does not mean ‘from the countryside’, but rather ‘from our own country’, meaning England.

To record the choreographies as simply and understandably as possible, Playford developed his own notation system for the different steps and explained it in an enclosed legend. Eighteen editions of The English Dancing Master had been released by 1728. The later editions included up to 360 songs and dances. These are an especially important record of English and European cultural history, and they are played and danced even today.

– M. Ren.