Athletics, amusement and the arts – the king’s daily routine consisted not only of duties but also distractions in the form of different activities. Leisure pursuits were very important at Charles II’s court. In the twenty-first century, both tennis and playing instruments are common hobbies. However, the popularity of these pastimes is not a recent phenomenon. In the seventeenth century the nobility enjoyed these activities as well. How did a king spend his leisure time? Are there any differences from our current amusements?

For centuries horse racing has played a major role in England. Only the nobility had the right to participate in these events and therefore it was known as the ‘sport of kings’. This sport was extremely popular among the upper class as early as the sixteenth century. However, during his reign, Charles I opened the sport to the common people and made it possible for them to take part in the public races. The King held these races in Yorkshire, Enfield, Chase, and Croyden.

Nevertheless, after Charles I had been beheaded, the ‘royal’ sport was forbidden until the coronation of Charles II. The son of Charles I was a patron of equestrian sports and responsible for their revival. The King was a gifted rider himself and enjoyed competing in races. Therefore, he spent a lot of time on the racetrack.

This etching by Francis Barlow shows the last race that Charles II attended before his death. The king and his guard are situated in his royal box while the race is in full swing. The title and the date of the publication can be found in a cartouche, which is surmounted by a crown. Furthermore, a poem, located at the bottom of the etching, praises the noble sport of horse racing and the king.

– N. Bo.

Happy Hunting: Charles II on the Hunt

Over time hunting, once necessary to survive, developed into an activity mainly reserved for the upper class. Hunting lodges were built for aristocrats, who then hunted wild game in the forest. Their hunting trophies were displayed and used as decoration in the castles.

According to Samuel Pepys’ diary, Charles II liked to hunt and did so with great success. Furthermore, several illustrations provide information about the king’s favorite activities during his leisure time. In this drawing, Charles II, dressed in full hunting attire, is chasing a rabbit with his hound. To the dismay of two women, the fleeing hare is headed towards them. Frightened, the ladies are pulling up their dresses to run away quickly. Since it was not allowed for ladies to show their leg, the drawing thus has a comical and erotic note. This could be an allusion to the king’s erotic hunting of the women of the royal court.

– N. Bo.

“The King beat three, and lost two sets, they all, and he particularly playing well, I thought.”

(Samuel Pepys, Diary, 28 December 1663)

Tennis originated from the sport ‘Jeu de Paume’, in which a ball was hit against walls into the opponent’s side of the court. The game was played bare-handed (the name derives from the French paume). The racket was invented in the sixteenth century, and this caused the game to grow in popularity. Originally, the game was the sport of the clergy. However, when the nobility became more interested in this pastime, it became the sport of kings.

During the reign of Charles II, tennis was one of the most popular sports in England. In 1634 a total of four tennis courts were situated in Whitehall Palace, the royal residence in London. Charles I and his son, Charles II, were fond of the sport themselves. Allegedly, the two of them got up at five or six in the morning to play tennis.

Charles II’s younger brother James also enjoyed playing tennis. This etching shows the seven-year-old in tennis attire. He is holding a racket in his hand and beside him two tennis balls lay on the ground. Several spectators have gathered in the stands behind the young aristocrat to watch him play. Nevertheless, they might have been less interested in his athletic abilities than in his position at court. Correspondingly, the book from which the image is taken, praised the young Prince James highly and highlighted his royal origins.

– N. Bo.

After breaking a sweat during sport activities, one could unwind by taking a break in fresh air.

“[I saw] The park, formerly a flat and naked piece of ground, now planted with sweet rows of lime trees; and the canal for water now near perfected”

(John Evelyn, Diary, 9 June 1662)

Gardens served various purposes in seventeenth century England. They could be kitchen gardens but also places for retreat and leisure. These so-called ‘privy gardens’ allowed aristocrats to enjoy the company of their friends and family in private. The painting depicts the garden at Hampton Court Palace where Charles II and Catherine of Braganza spent their honeymoon in 1662.

Charles II was interested in renovating both the castle and the garden. This image shows the gardens with a view of Hampton Court Palace’s east facade. Several rows of lime trees line a long, narrow channel. Charles II commissioned this canal, known as ‘Long Water’, which was excavated between 1661 and 1662. The lime trees for the avenues were imported from the Netherlands. This was different from typical English garden design. The gardens at the Palace of Fontainebleau in France and Honselaarsdijk in Holland may have been a source of inspiration.

– S. Me.

As early as the Seventeenth century people already used cosmetics and other beauty products to prepare themselves to appear in public. Thus, getting ready and presentable took up much of an aristocrat’s time between his or her appointments. Good looks were essential for all members of the court.

Alongside new fashions Charles II also brought perfumes and cosmetics back from his exile in France. The demand for such products increased due to a greater willingness to invest in one’s hygiene and beauty. Alleged experts offered solutions to get rid of blemishes. These advertisements were distributed through flyers or pamphlets.

The leaflet shown in the picture is an example of such advertisements and promotes a beauty tonic. One’s skin was supposed to become fairer, smoother and free from flaws such as freckles. Illustrations of tools that were used to produce cosmetics surround the text and give it a pseudo-scientific air.

Although these advertisements emphasized their positive effects, such ‘miracle remedies’ could be toxic. Oftentimes harmful ingredients like belladonna or mercury were used due to insufficient knowledge of their danger.

– S. Me.

You Live and Learn: Further Education at Court

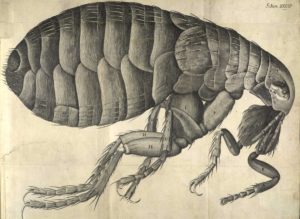

King Charles II was not only interested in parties and horse races but also in science. He continuously expanded his library and supported the Royal Society of London for Promoting Natural Knowledge, which was founded in 1660. The Society, whose twelve founding members wanted to advance natural philosophy, still exists to this day.

This microscopic view of a flea was featured in the Micrographia, the primary scientific work of Robert Hooke (1635–1703). Hooke was a member of the Royal Society and its Curator for Experiments. His book depicts microorganisms that he observed through his microscope. Through enlargements of these organisms, he made them visible to the naked eye.

Due to the images that provided a fascinating glimpse into a previously hidden world, Hooke’s book was very popular. The flea is shown in its smallest detail. This must have looked hyper-realistic, and the insect must have seemed almost alive to Hooke’s contemporaries. However, not everyone was enthusiastic about the flea. Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle, for example described it as a ‘monster of art, [rather] than a picture of nature’. Nevertheless, the Micrographia remains a work of great scientific and artistic importance.

– N. Bo.

The King had a wide range of interests in various fields. Thus, he was not only fond of reading books, but also music appealed to him.

“There was at Court a certain Italian, famous for the Guitar; he had a Genius for Musick […] the King’s relish for his Compositions had given that Instrument such a Vogue, that every Body play’d on it, well or ill; and one was as sure to see a Guitar on the Toilets of the Fair, as either Red or Patches.”

(Abel Boyer, Memoirs of the life of Count de Grammont, London 1714, p. 177)

Mary (‘Moll’) Davis is looking seductively at the viewer. The actress and mistress of the king was much admired during her lifetime. The print shows a portrait by Sir Peter Lely, the court painter. Davis is sitting, turned towards the viewer. She is wearing a loose dress with a low neckline and her hair is short and in curls. Lely has depicted her with a guitar as she was well known for her musical talent.

Charles II devoted himself to the arts, including music. He was not only a connoisseur but also a musician himself. As a result, he learned how to play the guitar. Due to his preference for this instrument, he hired the prestigious guitarist, Francesco Corbetta. Through his presence, the English court became well-known for its superb guitar music. Playing guitar was very popular during the reign of Charles II, especially since it was a suitable instrument for playful competitions between courtiers. Therefore, the nobility often studied guitar as part of their education.

– S. Me.

Keen Collector: Charles II as Art Collector

The fine arts played an important role in the life of Charles II. From a young age he was surrounded by his father’s remarkable art collection. This painting by Raphael was part of Charles’ I collection. It shows the Holy Family consisting of Mary, her mother Anne, the infant Jesus, John the Baptist, and Joseph. The work is also known as La Perla (in English ‘The Pearl’) because Philip IV of Spain allegedly proclaimed on receiving the painting, ‘This is the pearl of my collection’.

The King of Spain acquired the painting through the so-called ‘Commonwealth Sale’. Following the execution of Charles I in 1649, the authorities were able to sell a great part of his collection. After Charles II returned to England in 1660, he made a great effort to get the royal collection back. Despite several royal edicts demanding the restitution of the artworks, he was not able to recover all of them. One of these unreturned works was Raphael’s La Perla.

Charles II compensated for these losses by purchasing and commissioning new works. In this way the royal collection continued to grow.

– S. Me.