Hours of lust followed rousing parties and spectacular performances. While Charles II cultivated loyalty to his country during the day, he was not concerned with marital fidelity during his nocturnal affairs. Harmless flirtations on the part of the king could mean advancement to the rank of nobility for the chosen ladies. Thus, muses and mistresses competed with each other, became duchesses, and were often more popular among the people than the queen. All of them managed to do something that the queen could not – they gave their king children. Who were these women? What was the key to the royal heart? And what happened when illegitimate offspring were born in these circumstances?

Delight and terror, pleasure and torment sometimes lie close together. Carlo Dolci’s painting presents itself as both attractive and repulsive. A seductive woman attracts the eye but shocks the viewer by the composure with which she presents the severed head of a man on a plate.

The woman is Salome, stepdaughter of the biblical King Herod. She has enchanted him with her dance to such an extent that he is willing to grant her every wish. On her mother’s advice, she demands the head of a particularly prominent prisoner: she demands the execution of a holy man, John the Baptist. The cruelty of the beauty offers a powerful contrast to her lovely appearance.

Charles II received this painting as a gift and was so taken by it that he had it hung in his bedroom. Presumably, the work appealed to him so strongly because he favoured ‘femmes fatales’ who bring even kings to their knees.

– M. Kl.

The women Charles II fell for were very different from each other. Some of them came from the nobility; others were commoners. Their portraits reflect a whole spectrum of women’s roles. These will be examined more closely in the following section. The children born of the king’s extramarital affairs were viewed with suspicion. They enjoyed all the advantages that royal children could expect – the only thing to which they had no right was the throne.

“the King do mind nothing but pleasures […] that my Lady Castlemaine rules him, who, he says, hath all the tricks of Aretin that are to be practised to give pleasure.”

(Samuel Pepys, Diary, 15 May 1663)

According to Samuel Pepys’ diary, Charles II boasted that his mistress Barbara Villiers (also known as Lady Castlemaine) had mastered “all Aretine’s tricks” – that is, the erotic repertoire that the Italian Renaissance author Pietro Aretino had not only described but also depicted in pornographic illustrations. Amazingly, however, Barbara Villiers is shown in this painting wearing the typical robe of the Virgin, a flowing red dress with a blue upper garment and veil. Seated next to her is one of her sons, probably Charles FitzRoy, whose pose alludes to the baby Jesus. Apparently, with this work Barbara wanted to show the world that her children were more than just illegitimate offspring; through his illustrious father, the little child had quasi-divine status.

Barbara came from a noble but impoverished aristocratic family. In 1659 she married Roger Palmer and went with him to the court of the king, who was still in exile at the time. Shortly afterwards, she began an affair with Charles II. After officially separating from her husband in 1662, she bore the king a total of six children over the course of their long relationship. In the 1670s, Louise de Kéroualle replaced her as the king’s favourite.

– M. Kl.

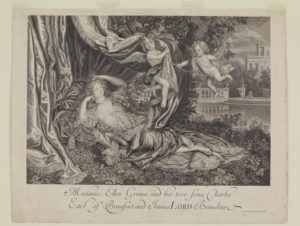

By her own account, Nell Gwyn grew up in a brothel, served alcohol there, and probably worked as a sex worker herself. She was known for her quick wit and spirited personality. After her first small roles in the theatre, she developed into an up-and-coming star. She was not only successful as an actress, however, but also in love. Each of her lovers was richer than the previous one – until finally, on a memorable evening at the theatre, she was even able to cast a spell over Charles II himself. She bore the king two sons, Charles (1670) and James (1671).

In the engraving, which reproduces a painting by Henri Gascar, the two children appear as winged cupids. The smaller boy holds a bow, the usual attribute of Cupid, the god of love. His older brother pulls back a rich curtain to reveal their mother reclining lasciviously in the grass. Nell Gwyn presents herself as a seductive Venus – in a nightgown she is said to have stolen from her rival, Louise de Kéroualle. The caption unmistakably alludes to Nell’s role at the royal court, as her name has been altered to “Ellen Groinn.” “Groin” is naturally a slightly oblique reference to the region of the king’s body that was particularly attracted to Ellen.

– M. Rei.

Charles Beauclerk was born as the first of the two sons of Charles II and Nell Gwyn on 8 May 1670. Since the king had no legitimate descendants, he paid a great deal of attention to Beauclerk. Nell urged her lover to elevate their joint children to the peerage. Thus, little Charles Beauclerk became Baron Heddington and Earl of Burford when he was just six years old. At eleven he was sent to France to be educated. There he learned French and military administration, among other things. In 1684, Charles II bestowed upon him the title Duke of St. Albans, thus elevating his illegitimate son to the highest rank of the nobility in the realm.

Godfrey Kneller’s portrait shows the handsome youth when he was about 20–25 years old. The picture was made around the time of his marriage in 1694. Charles married Diana de Vere, a famous society beauty and sole heiress of the Earl of Oxford, with whom he had twelve children.

– M. Rei.

Louise de Kéroualle never enjoyed the same degree of popularity among the English as her native rival Nell Gwyn. Although, or perhaps precisely because, Louise came from a French noble house and was well-mannered, the British were suspicious of her; among other things, they suspected her of espionage.

Louise was one of the ladies-in-waiting in France of the Duchess of Orleans, who was one of Charles II’s sisters who had married into the French court. As part of the duchess’s entourage, Louise visited England in 1670 and soon became one of the king’s mistresses. Their son was born in 1672, and in 1673 Charles bestowed the title of Duchess of Portsmouth on his paramour. Louise thus achieved a much more rapid social rise than Nell Gwyn, who courted the king’s favour at the same time.

The rivalry between the two women is expressed in their portraits. Both had themselves painted by the French artist, Henri Gascar – and both in very similar poses, lounging lasciviously in a landscape. While Nell Gwyn presented herself as Venus, however, Louise de Kéroualle chose the role of Mary Magdalene. According to legend, this saint had lived for a long time as a hermit in France; far from civilization, she clothed herself only in her long hair. While Kéroualle may have identified herself with the “French” saint, she used the legend primarily to show of her long hair on bare skin in a most advantageous way.

– M. Rei.

Charles Lennox was the son of King Charles II and Louise de Kéroualle, born on July 29, 1672. At the tender age of three, his father elevated him to Duke of Richmond and Duke of Lennox. The title of duke denoted the highest rank of the nobility. Nell Gwyn was outraged that the son of her French rival was able to enjoy this title so young (1675). Her own son Charles, on the other hand, had to wait until the age of barely fourteen before being elevated to Duke of St Alban’s in 1684.

Kneller’s portrait also illustrates an honour denied to Nell’s sons: the king admitted Charles Lennox to the exclusive Order of the Garter in 1681. Accordingly, the embroidered cross of the order adorns his velvet jacket – very similar to a portrait of his father. In this point, too, Charles Beauclerk had to show considerably more patience, because he was not admitted to the Order of the Garter by his own father, but only in 1718 by King George I.

– M. Rei.

“She perform’d that so Charmingly, that not long after, it Rais’d her from her Bed on the Cold Ground, to a Bed Royal.”

(John Downes, Roscius Anglicanus)

Mary („Moll“) Davis, like Nell Gwyn, was an actress as well as a gifted guitarist. She was one of the most important actresses at the Duke’s Theatre in London. Her affair with Charles II began as early as 1667 but lost intensity after he met Nell. It was not until 1673 that she gave birth to her first (and Charles’ last) child – a daughter named Mary.

The court painter, Peter Lely, did not portray Moll Davis in any recognisable role but emphasised her erotic appeal. She appears half undressed and coquettishly covers herself with a blue shawl. With a seductive gaze, she gazes on the viewer as if inviting him into her bedchamber. The bulbous, precious vase on which Moll’s right hand rests may allude to her pregnancy.

– M. Kl.

The future Lady Mary Radclyffe was born on 16 October 1673, the daughter of Moll Davis and Charles II. She grew up surrounded by aristocrats, theatre people, playwrights, artists, and poets and began acting at a young age; her role model was, of course, her mother. The extravagant costume in which she is portrayed betrays her penchant for theatricality. Otherwise, however, little is known about Charles II’s last illegitimate child. Through her marriage to Edward Radclyffe, 2nd Earl of Derwentwater, Mary rose to the lower nobility in 1687. After his death, she married twice more (each time to commoners) and died in Paris in 1726.

Looking back at the lives of Charles II’s illegitimate offspring, it is clear that the king did not treat his children equally. Rather, the status of the mother and the sex of the child seem to have influenced the intensity of his affection. The sons generally possessed a greater interest for him than his daughter, which was expressed by the fact that he gave them significantly more prestige through increases in rank. But even in this, there were differences. As the son of a noblewoman, Charles Lennox had a much easier time rising to the highest nobility than the sons of the bourgeois Nell Gwyn.

– M. Kl.