Image is power. The line separating the man and the king is thin and made of crimson velvet, perfumed wigs, and fabrics imported from the East. Each morning in the royal chambers, the most exclusive rooms in England, the man Charles transformed into King Charles II of England. What did these rooms look like, what were these processes, and what kind of fashion was commonly worn by the king and his court?

Privilege of the Nobility: The Sleeping Alcove

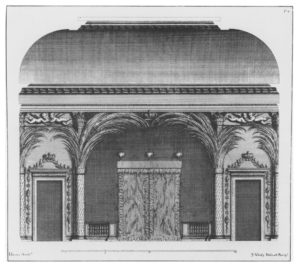

What is meant by the term “alcove”? At the time of Charles II, it was customary for higher-ranking aristocrats to sleep in magnificently decorated alcoves. This was a windowless room connected to the anteroom by a large wall opening and containing a bed.

An alcove is thus a separate sleeping room from the bedroom proper. Charles II had become familiar with this room arrangement during his exile in France. Immediately after his return to London, he had an alcove built into his bedroom during a remodelling of Whitehall Palace in 1660/61.

Although, no views of this have survived, an impression of the appearance of a royal alcove can be gained from a drawing by John Webb from 1665. The architect designed this alcove for the royal palace in Greenwich. The entrance to the alcove was intended to be dramatically staged and is flanked by two carved palm trees. Documents reveal that the alcove at Whitehall Palace, on the other hand, was decorated with carved angels, eagles, and curtains. This elaborate room decoration was destroyed in a fire in 1698, while the design for Greenwich was never realized due to a lack of funds.

– H. Bi.

The Kingʼs Bedchamber: More than just a bedroom?

The photograph is a photograph of the bedroom furnishings of King James II. This is what Charles’ brother’s state bedroom at Whitehall Palace might have looked like. Today, however, the furniture is no longer in its original location in London but is on display at Knole House in Kent. These pieces are particularly distinguished by the cloth of gold, embroidery and tapestries.

Charles II introduced the so-called ‘Bedchamber Ceremonies’ – a custom that originated (like the alcove) from the French court of Louis XIV. These were a morning ceremony in the king’s bedroom, the lever (rising), and an evening one, the coucher (going to bed). At about eight o’clock in the morning, the monarch was awakened and dressed by his servants, receiving various visitors to discuss political as well as private matters. The coucher took place at 11 pm. Here the king was undressed.

However, the bedroom was open not only to the courtiers, but also to the royal pets. The monarch owned many King Charles Cocker Spaniels (the breed is named after him). It was impossible to imagine the king’s bedroom without the dogs, because they were allowed to spend the night there. A man named James Jack is said to have had the task of making sure that the dogs did not jump on Charlesʼ bed and disturb his night’s rest.

“On the King`s death in 1685, John Evelyn wrote in his diary how Charles had enjoyed `having a number of little spaniels follow him and lie in the bedchamber, where he often suffered the bitches to puppy and give suck, which rendered it very offensive, and indeed made the whole court nasty and stinky`”

(John Evelyn, Diary, 6 February 1685)

– H. Bi.

Absolutist Ideology in the King’s Bedroom

In 1660 and 1661, Charles II had his London residence, Whitehall Palace, remodelled. An essential part of the renovation was the construction of an alcove in which the king could sleep. Charles II also purchased new furniture for his state bedroom and commissioned the painter John Michael Wright to create a programmatic ceiling painting.

The lower half of the oval is dominated by an angel with a banner proclaiming the message ‘TERRAS ASTRAEA REVISIT’ (Astraea has returned to earth). Astraea, a symbol of justice, is enthroned in the upper half of the picture in a flowing white dress. Her head is backed by a halo of rays. She gestures to a portrait of Charles II, which is held by three small putti. Another putto presents a set of scales as a sign of justice.

In addition to the portrait, there are other pictorial elements that allude to the English monarch. These include the star at the upper left edge of the picture and the oak tree in the lower third of the picture. The star appeared in the sky during the daytime at Charlesʼ birth and was interpreted (like the Star of Bethlehem) as a sign of the special importance of the new born. The tree, on the other hand, recalls the legendary rescue of the king by the royal oak.

The core idea of the painting goes back to the ancient myth of the four ages, which is found, among other places, in the first book of Ovid’s Metamorphoses. According to this legend, there are four ages of the world, in which the state of the earth degrades from the first, Golden Age to the fourth, Iron Age. Thereupon Astraea departs from the world, leaving it in chaos. According to Virgil’s Eclogues, the return of Astraea ushers in a new Golden Age in which humans can live in peace and happiness. Wright’s painting can thus be interpreted to mean that the return of Charles II to England heralds a new Golden Age for the country.

– H. Bi.

This caricature makes fun of the French ‘Sun King’ Louis XIV. The cartoonist refers to the famous portrait of Louis XIV painted by Hyacinthe Rigaud in 1701. This figure is quoted on the right side of the sheet. However, Thackeray dissects the monarch into his individual parts, so to speak. Thus, the image depicts a bald man in the centre and a manikin dressed in the ruler’s insignia the left side. In bringing both parts together on the right side of the picture, the viewer recognizes the complete monarch, who stands out above the ordinary mortals only by means of his pompous clothes and towering wig.

In the early modern period, a king was thought to possess two bodies, one natural (mortal) and one political (immortal). The bald man in the centre of the painting represents the monarch as the body natural. Through the insignia of office on the left, which give the king dignity, Louis XIV is shown as body politic on the right. Through this caricature, however, Thackeray deconstructs the illusion of the monarch.

The morning ceremony of the lever, maintained by both Louis XIV and Charles II, allowed courtiers to participate in the spectacle of royal dress. Before their eyes, an ordinary person was transformed into an absolutist ruler through ostentatious robes and insignia of rulership – in keeping with the old saying ‘the clothes make the man’.

– H. Bi.

In this painting by Simon Verelst, King Charles II presents himself wearing the traditional garb of the Order of the Garter. Around his neck the collar of the order can be seen, showcasing the ‘Great George’, a depiction of the patron saint of the order slaying a dragon. The king is wearing a blue garter below his left knee from which the order derives its name and which serves as a way of identifying other members. While the king was quite famous for his modern sense of style, he had a particular preference for portraying himself wearing the garb of the Order. There are several possible reasons for this.

Firstly, after his coronation Charles restored the Order. The Order of the Garter was and remains to this day one of the highest-ranking orders in England. Charles’ decision for its reinstatement was primarily made to emphasize the traditional aspects of his new reign. Second, while in exile in France the young Charles did not have access to the royal insignia; but what he did have access to were the regalia of the Order of the Garter, which might have served as symbols of hope and solace for him.

In April of 1661 Charles mandated the traditional trousers of the uniform be once again made of silver thread, which had previously been used for parts of the original uniform. Not only did his decision emphasize his respect for tradition, it also established a parallel to the similar uniforms of the French Order of the Holy Spirit. Even though Charles wore this traditional garb only for specific occasions, he still displayed his loyalty in other, more subtle ways; many of his coats’ sleeves were decorated with an embroidered badge of the order. The traditional uniform consists of the collar of the order, decorated in gold as well as red and blue embroidery; the eponymous garter, worn below the left knee by men and on the left arm by women; the so-called George, a brooch depicting St. George during his fight with a dragon; a coat made of blue silk bearing the St. George’s Cross on the left sleeve; and a black silken hat decorated with a large, white ostrich feather as well as several black egret feathers.

– M. We.

Honour, Duty, Fashion: The Order of the Garter

This drawing by court painter Peter Lely shows two fully uniformed knights of the Order of the Garter who are presumed to be Henry St. George, Herald of Richmond, and Thomas Lee, Herald of Chester. This work is part of a series by Lely of the contemporary members of the Order. Some illustrations have unfortunately been lost over time.

The Order of the Garter is the highest-ranking order in England and was originally founded by King Edward III in 1348. The tales of King Arthur and his Round Table served as inspiration. The Order consists of twenty-four members including the reigning king who serves as both sovereign and highest-ranking member. Originally only men of noble blood were able to join; today anyone regardless of gender or social background may become a member. An invitation to join the order is made in recognition of extraordinary service to the nation. Announcements of potential candidates are made on 23 April, which is also known as St. George’s Day. St George is the patron saint of the Order as well as of England itself. The motto of the order is ‘Honi soit qui mal y pense’, which is French for ‘Shame on him who thinks this evil’. The origins of this motto are unknown. Each June on the so-called ‘Garter Day’, England observes one of its oldest ceremonial traditions. On this occasion all members of the order gather in St. George’s Hall at Windsor Castle for a procession, the knighting of new members, a church service, and a banquet.

Lely’s drawing shows two heralds of the Order. Heralds usually function as organisers of tournaments, diplomats, and ambassadors; their role was to be the public face of the order. They wore black breeches and red and blue tabards. The latter were commonly decorated with lions, harps and unicorns embroidered in gold, which are the heraldic symbols of the kingdoms of England, Ireland, and Scotland respectively. Furthermore, the embroidered lilies refer to the English claim to the French throne.

– M. We.

A Glimpse into the Wardrobe of the English Lords

The doublet seen here is exemplary for showcasing the kind of fashion commonly worn at the court of Charles II. This article of clothing is the wedding suit of Edmund Verney, who married Mary Abell in Westminster Abbey in July 1662. Edmund was part of the noble Verney family. Their most prominent member, Sir Edmund Verney, was a knight marshal and a personal favourite of king Charles I.

This doublet is a typical example of the extravagance found in the court fashion of the 1660s. Popular trends of the time were influenced heavily by France and the Netherlands, which becomes clear when looking at the doublet’s combination of a wide petticoat and breeches. Additionally, this article of clothing features six different kinds of ribbons and braids in violet, pink, silver and white. Altogether, this amounted to 144 meters of trimming.

Popular fashion trends of the preceding era, featuring a characteristically wide waist, slowly gave way to the internationally inspired style favoured by Charles II with its long, vertical lines, low waistline, and wide shoulders. Other popular details included decorative ribbons, especially around the waist, as well as slashed sleeves, both of which were adapted from French court fashion.

By 1666, Charles II expected every courtier to dress in a long coat, petticoat, cravat, wig, and riding breeches, based on the style of the French king, Louis XIV. In 1680 this attire was turned into the standard for formal clothing and went on to dominate men’s fashion for the following century.

“A courtier put both his legs through one of his Knees of his breeches, and went so all day.”

(Samuel Pepys, Diary, 6 April 1661)

– M. We.

What Did a Woman of Fashion Wear?

The so-called silver tissue dress is one of the most famous and well-preserved articles of clothing from Charles II’s age. The dress obtained its name because of its fine silk interwoven with silver threads. The original owner was likely Lady Theophilia Harris, the wife of Sir Arthur Harris of Hayne, Devon, and daughter of Sir John Turner, a successful lawyer.

Typical elements of women’s fashion during Charles’ reign included tight, long bodices; low, sometimes off-the-shoulder necklines; wide, elbow-length sleeves; and long, wide skirts. As with men’s fashion, these were influenced by popular French trends. This is especially true for the low necklines of the period. A popular feature is the usage of metallic threads which were used to decorate sleeves, necklines, bodices, and skirts. In addition to dresses, tailors would also incorporate these valuable threads into accessories like shoes or gloves. Additional trends not seen on this dress are long rows of ribbons down the middle of the bodice, as well as shimmering satin dresses and heavy brocade dresses.

Clothing like the silver tissue dress serves as an early model for the deshabillé-robe, also known as mantua or manteau, which originated around 1680. This robe would go on to dominate women’s fashion in England, France, Germany, and many other European countries for the next two centuries.

– M. We.