Whether state visits with grandiose ceremonies, ransom negotiations, or bribery attempts – daily royal business could be full of surprises. A public hearing at Whitehall Palace was a very different affair than a strategic discussion in the king’s study. Each one of these occasions required an appropriate setting. These rooms had to be lavishly and expensively furnished to adequately present Charles II. Where did the king find inspiration for the decoration of his palaces? And was all that glittered really silver?

WHERE? Whitehall and Windsor as Prime Locations

Windsor Castle is still the largest and oldest inhabited castle in the world. Charles II had the medieval building lavishly modernized and made the scenically situated castle his most important summer residence. The primary focus of this view is the Star Building, newly erected in 1675/76, which is particularly highlighted by the fall of the light. The name of the building refers to the fact that the facade was adorned with a huge, gilded star. On the one hand, this referred to the star of the Order of the Garter, whose most important meeting place was (and still is) Windsor Castle. On the other hand, the star could be understood as an allusion to the unusual celestial phenomenon at Charlesʼ birth. The fact that a star had been visible in the sky during the day on his birthday was considered a sign of Heaven’s special favour. Johannes Vorsterman’s painting subtly embeds this meaning into the scene through the direction of the light. The sun specifically illuminates the Star Building, which acts as a sign from God glorifying royal power.

– L. Kl.

Splendour and glory demonstrated the power of a king. Charles II used the baroque decoration of the newly refurbished rooms in Windsor Castle as a means of displaying his splendour. Most of these room furnishings were destroyed in the nineteenth century but are documented in watercolours by Charles Wild.

St George’s Hall, which no longer exists in this form, served as the throne room and meeting place of the Order of the Garter. The name of the room was an homage to the holy dragon slayer, George, the patron saint of the order. The Baroque ceiling painting of the hall was designed by the Italian, Antonio Verrio, one of the most important Barqoue painters at the royal court. The central painting of the ceiling presents Charles II as god-like on a rainbow. Beginning in the Middle Ages, Christ has been depicted on a rainbow in images of the Last Judgement. By adopting this pictorial formula, Verrio glorified the seemingly infallible judgment of the king.

If one considers the hall as a counterpart to the Royal Chapel, which was directly opposite, the importance of the hall as a means of representation of the king becomes even clearer. Charles II succeeded in visualizing the divine graces of his reign not only through the ceiling painting, but also through the juxtaposition of throne and altar.

“Virio the Painters Invention is likewise admirable, his Ordnance full & flowing, antique & heroical, his figures move; and if the walls hold […] the work will preserve his name to ages.”

(John Evelyn, Diary, 16 June 1683)

– L. Kl.

Charles II had two audience chambers at Windsor Castle, the Presence Chamber and the Privy Chamber. The Privy Chamber, whose appearance has been preserved in this watercolour by Charles Wild, was reserved for the most distinguished visitors. The oil paintings on the walls, ceiling paintings, and rich gilding were meant to impress guests. In Wild’s watercolour, the king’s throne is the centre of attention, just as it was the focus of every audience. Antonio Verrio created the ceiling painting (since destroyed) between 1676 and 1678. It depicts the reinstatement of the Church of England in 1660, which was a central and important part of Charlesʼ II restoration. Anyone who received an audience with the king was thus reminded of his dual, spiritual and secular leadership roles. Since King Henry VIII turned away from Catholicism, English monarchs were (and are) also heads of the Anglican Church.

“On the Ceiling is represented the Establishment of pure Religion in these Nations, on the Restoration of King Charles II. in the Characters of England, Scotland, and Ireland, attended by Faith, Hope, Charity, and the Cardinall Virtues; Religion triumphs over Superstition and Hypocrisy which are drove by Cupids from before the face of the Church; all which appear in proper attitudes, and the whole highly finished.”

(Description of the mural by Joseph Pote in ‘Les Delices de Windsore’, 1755)

– L. Kl.

Windsor Castle served as the monarch’s country residence, but it was also designed to receive state guests. The most important audiences, however, took place at his London residence, Whitehall Palace. Since the building was almost completely destroyed in a fire in 1698, only a few surviving furnishings can give an impression of its former splendor.

Although Antonio Verrio’s Sea Triumph of Charles II hung in Whitehall Palace from 1688 at the latest, it is also related to Windsor. It served as a demonstration of skill by which the Italian newcomer, Antonio Verrio, successfully landed the lucrative commission for twenty ceiling paintings for Windsor Castle.

This work was probably inspired by the Third Anglo-Dutch War, which was fought from 1672 to 1674 and ended with the Treaty of Westminster on 9 February 1674. Verrio depicted King Charles II in antique armour. The female allegory of victory places a helmet on his head, while a male personification of time holds a laurel wreath above him. Charles appears as a victorious Roman general, who claims dominion over the seas. At his feet sit three women, who represent his three realms, England, Scotland, and Ireland. Two winged cherubs with darker skin on the right may symbolize England’s colonial expansion. The Latin inscription states that Charles’ fame extends even to the stars.

Charles was familiar with his father’s substantial art collection and was aware that art does not just serve as decoration, but also as a demonstration of power. The Third Anglo-Dutch War did not end as triumphantly as Verrio would like the spectator to believe. Peace with the Netherlands was more of a financial necessity, rather than the result of successful English warfare and therefore, it was all the more important for Charles to demonstrate his political and military strength to his subjects and visitors.

– T. Hi.

Appearance and Reality: The Display of Power, Money, and Glory in the Image of Versailles

The government of Charles II “brought a politer way of living that passed into luxury and intolerable expenses”

(John Evelyn, Diary, 4 February 1685)

The various rooms of the palace had specifically defined functions. They regulated not only access to the monarch but reflected the status of the visitors as well. The more distinguished the guest, the farther he was admitted into the chambers. The closer a room was to the audience room, the most important room at court, the more expensive and magnificent the interior became.

The king chose the most valuable materials such as gold and silver, which were used for threads in tapestries, gilded candelabras, chandeliers, drinking cups and mirrors to show subjects and foreign visitors that the king’s treasury was well-stocked. An especially common set of ‘state furniture’ was a combination of table, two candelabras and a mirror, often placed between two windows. The silver reflected the candlelight, which created a sparkling effect. This made the room look opulent, expensive and important, even though the English silver furnishings, in contrast to those at Versailles, consisted largely of silver-plated wood. The monogram of Charles II was attached to all these objects in order to preserve the memory of the glory of his reign even after his death.

– T. Hi.

WHO? The Ambassadors and the Art of Diplomacy

Art not only displays status but also serves as a diplomatic tool. Lorenzo Lotto’s portrait of the Venetian merchant Andrea Odoni is an example of this; Charles II received it as a diplomatic gift.

Like Charles II, Andrea Odoni was also a passionate art collector. In the foreground we see a bust of Hadrian and a fragment of an ancient figure of Venus from his collection. The statuettes and fragments in the background are probably plaster casts of Roman originals. Odoni is wearing a cross pendant around his neck and holding a small figure of Diana of Ephesus in his right hand. This contrasts paganism with Christianity. The material decay of the sculptures also can be seen as the perishability of human works compared to enduring nature.

The painting was part of the so-called ‘Dutch Gift’. The Provinces of Holland and West Friesland presented it to Charles II in 1660 shortly after he ascended the throne. The king obviously admired the portrait and hung it in the Green Chamber at Whitehall Palace, which was next to his private bedchamber. Nevertheless, the gift did not achieve the desired diplomatic effect; it could not stabilize the fragile relationship with England. Any hope for peace was abandoned when the Anglo-Dutch War broke out again in 1665.

– L. Sch.

England had been a minor player global politics, but when Charles II ascended the throne, the country experienced an economic upswing. The king’s wife, Catherine of Braganza, played a leading role in this. Her dowry, including money and trade privileges with the East Indies helped expand English trade overseas. She also brought the colonial cities of Bombay and Tangier (Tanger) to the marriage. The latter initially was a strategically fertile trading post. However, the understaffed garrison there soon was soon overwhelmed. In 1678 Moroccans captured over 100 Englishmen and garrison soldiers. Sultan Mulai Ismail then sent Mohammed Ohadu to England to negotiate with Charles II.

The ambassador arrived in London in November 1681 and stayed there until July 1682. Probably during this time, Godfrey Kneller of Lübeck painted the diplomat’s portrait. However, the inscription dates this impressive work to 1684. Kneller depicted the well-traveled Moroccan ambassador on horseback in the manner of a European ruler. In doing so, he recalled Ohadus’ much admired riding skills. Ohadu, for his part, praised English architecture and theatre. At the universities of Oxford and Cambridge he communicated with professors of Arabic in his native language.

Despite the successful cultural exchange, the Sultan’s reaction was ultimately disappointing. The ransom for the captured soldiers was unaffordable. In 1684 England surrendered its claim to Tangier. Unfortunately, the trade relationship with Morocco declined under Charles II.

– L. Sch.

HOW? Being Heard: An Audience with Charles II

The following paintings make us aware that the question of who was allowed to visit the king often led to a lengthy how. Then as now, state visits were meticulously planned. This large painting by François Duchatel shows the public entry of Claude-Lamoral of Ligne into London on 13 September 1660. The Spanish King Philip IV sent the prince as his representative to congratulate Charles II on his accession to the throne after he returned from exile.

A view of medieval London before the great fire of 1666 extends into the background. On the right, the Tower of London, the most important landmark of the city at that time, is visible against the sky. The procession of horsemen and carriages of the Spanish embassy is just starting to move between the fortifications and the embankment. Clouds illuminated by the sun seem to soak up the tension of the cheering crowd. As is customary on official state visits, the English king provided ships to transport his guests from the continent across the Channel. In this case, Charles II sent his most precious galleys to Ostend. One of the pleasure barges is visible at the left edge of the picture.

Visits from foreign ambassadors served as a barometer of social acceptance and royal reputation at home and abroad. A master of ceremonies always monitored these events carefully. Both Charles II and his guests attached great importance to such visits.

– L. Sch.

Claude-Lamoral of Ligne enjoyed the status of an extraordinary ambassador, hence a solemn entry into the city was necessary. An official audience with the king took place as well. However before the ceremonial gathering, it was important to accommodate the tired guests appropriately upon their arrival. Claude-Lamoral I and his entourage were entertained for three days at Camden House, as usual at the expense of the host, Charles II. On 17 September, the King finally received the Spanish ambassador at the Banqueting House, the great ballroom of Whitehall Palace.

Gillis van Tilborch immortalized this solemn moment in a large painting. It impressively conveys the joyful tension of the audience. The English courtiers crowd closely together in the back of the hall and on the gallery. The lavishly dressed members of the Spanish embassy are standing in a row in front of the throne, which is covered by a large, red canopy. As a respectful gesture towards his guest, Charles II rises from the throne. He greets the Prince of Ligne and holds a letter he has just received from Philip IV in his hands. The congratulations to the recently crowned King of England are accentuated by festive music. The expectation of the crowd is palpable; they have come to see and be seen. Even Charles II probably remembered these splendid events for a long time.

– L. Sch.

Charles II met people from all different walks of life at his audiences. He not only met with high-ranking diplomats and nobles, but also received commoners and even the sick. This oil sketch shows an audience of students, teachers and administrators of Christ’s Hospital, a London educational institution for children who had lost one or both parents.

This orphanage had already been founded by King Edward VI. Charles II promoted the establishment of a special “Mathematical School” where pupils were to be trained for service in the Royal Navy. Verrio’s oil sketch served as a preliminary study for a monumental mural to be installed in Christ’s Hospital to express the institution’s gratitude to its royal benefactor.

Although Verrio’s work does not depict an identifiable room, it can be assumed from documentary sources that this audience took place in a royal palace. The spatial arrangement of the figures and their clothing illustrate the hierarchy. The history painting thus not only provides information about the king’s charitable activities, but also records the courtly ceremonial of an official audience.

– L. Kl.

“Did business, though not much, at the office, because of the horrible Crowd and lamentable moan of the poor seamen that lie starving in the streets for lack of money – which doth trouble and perplex me to the heart. And more at noon, when we were to go through them; for then a whole hundred of them followed us, some cursing, some swearing, and some praying to us.”

(Samuel Pepys, Diary, 7 October 1665)

Part of the king’s duties was to not only receive visitors from near and far, but also to meet regularly with his ministers and high-ranking administrators. One of the latter is Samuel Pepys, who is best known today for his diary. This record gives meticulous details about the period between 1660 and 1669. It describes private matters, meetings with the king and historical turning points such as the outbreak of the plague of 1665 and the great fire of 1666.

Pepys worked his way up to the highest ranks of the royal navy with the help of his unusual work ethic, his many talents, and his valuable contacts, until he was eventually appointed Secretary to the Board of Admiralty. In this position, he answered only to the king. He advised Charles II regularly on all matters concerning seafaring and introduced extensive reforms to professionalise the navy after the devastating Anglo-Dutch Wars. In this context, he was essential in founding the Mathematical School of Christ Hospital. Furthermore, he established standards for the training, provisioning and medical treatment for officers and crew. He was so successful that he was called the father of the modern royal navy.

– T. Hi.

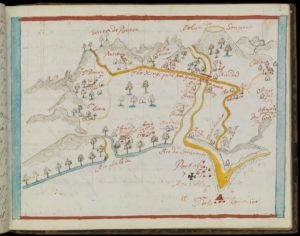

In 1681 the English privateer Basil Ringrose and his crew captured a Spanish derrotero, also called a waggoner. It was a book which contained maps and directions for seafaring. This derrotero was especially valuable because it contained much more detailed information about sailing routes than were previously known by the English. Ringrose translated and commented on the Spanish manuscript and provided drawings in ink and watercolour. The entire work is handwritten. It is comprised of the earliest descriptions and maps in English of the Californian coast from Cape Mendocino to Cape San Lucas.

No other copies of the South Sea Waggoner exist. The work was printed for the first time in 1992. Judging from its good condition, the manuscript was probably never used. Nevertheless, it is a rich source of information on seafaring and cartography in general, as well as on the native populations of the American continents, the trade in enslaved people, the plants and wildlife and the terrain of the Pacific coasts of North and South America. It is imaginable that the South Sea Waggoner could have been an object of discussion between Samuel Pepys, who was Secretary to the Board of Admiralty and King Charles II.

–T. Hi.