Pomp, ostentation, and power – terms that spring to mind when one thinks of the distant era of the Stuart monarchy. However, history books reveal a different picture. A civil war, the flight of the young king, his triumphant return, intrigues, and plots at court – this and more made up the reality of Charles II’s life.

This section will shed light on the monarch’s historical background and dares to look behind the imposing façade. Who was Charles II? What events shaped his reign? And what were the consequences of the simmering conflicts at that time?

A new head, a new king. Charles II nominally succeeded his father Charles I to the throne in January 1649, after the latter had been condemned for high treason and beheaded. It was, however, impossible for Charles II to take power.

During the 1640s England experienced a power struggle between the supporters of the king and Parliament. The resulting Civil War culminated in the execution of the king. Only in Scotland was his son, Charles II, recognized as the new king and crowned in 1651, whereas in England, Parliament took power.

The engraving shown here depicts the events of the year 1649 from a royalist perspective. The background depicts the Banqueting House of Whitehall Palace, the ceremonially hall of the royal residence in London. In front of the building a large crowd has gathered and is attentively watching the execution of Charles I. Streams of blood are shooting from his body, from which the head has just been cut. The executioner presents the head to the onlookers.

The upper scene of the engraving interprets the event as a martyr’s death. The body of the king is laid as if on an altar. The scene is crowned by a large portrait of Charles I, who is depicted in the manner of a saint.

An engraving celebrating the dead king in such a way was not allowed in England in this period. The inscription indicates that the engraving was made in the Netherlands (presumably in Amsterdam).

– K. He.

After the execution of Charles I, his son Charles II passed his exile mainly in The Hague. In 1650/51 he tried to regain the throne of Scotland. The invasion of England failed on 3 September 1651 at the Battle of Worcester, where Oliver Cromwell’s newly formed army finally defeated the royalists. Despite the defeat, Charles was able to escape from the parliamentary forces. He hid in the branches of an oak tree while Cromwell’s troops combed the whole forest.

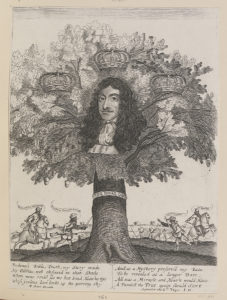

This engraving depicts the story of Charles II’s concealment in the tree. There is an oak in the centre of the picture, identified in an inscription as the ‘Royal Oak’. In the foliage there is a bust portrait of Charles II surrounded by three crowns. They symbolise three kingdoms of England, Ireland, and Scotland, which the king later regained. After his restoration to the throne, Charles liked to tell the story of his escape and turned it into a miraculous legend.

– A. Mo.

Charles II spent more than ten years in exile, many of them at the French royal court were his mother Henrietta Maria had been born. During his last period of his exile, Charles stayed at the Hague. He could count on family support because his widowed sister Mary lived there. She had been married to the governor of the Republic of the Seven United Provinces of the Netherlands.

“Long as my exile, sweet as my revenge!”

(William Shakespeare, Coriolanus, Act 5, Scene 3)

In 1658 after the death of Oliver Cromwell, who had ruled England as Lord Protector from 1653, Charles saw the opportunity to regain his kingdom. In May 1660, the English Parliament invited him to return to London. This engraving shows the banquet held at the Hague on the evening before his departure. At the head of the table on the right side of the picture, Charles II sits under a baldachin, surrounded by members of his family. Representatives of the States General of the Netherlands sit at an adjacent horizontal table. The engraving conveys an impression of the courtly ceremony of the period. It also captures the importance of this historical moment when Charles II’s long years in exile ended.

– F. vdDi.

The Restauration of the Monarchy

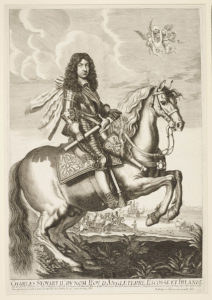

This engraving was published soon after Charles II returned from exile and depicts him (according to the caption) as King of England, Scotland, and Ireland. In order to put the engraving on the market as quickly as possible, the publisher edited an earlier image. Notably, the original engraving, designed by Elias Küsel, portrayed Oliver Cromwell. He was the nemesis of Charles II and had led the opposition to King Charles I during the Civil War.

The engraving now shows an equestrian portrait of Charles II instead of Oliver Cromwell. Two small angels hover in the upper right corner holding the king’s coat of arms. Apart from the insignia and the rider’s head, almost nothing has changed from the original. However, the second engraver lengthened the horse’s tail to cover up the signature of the original engraver, Küsel.

The engraving was probably made in Paris. The inscription in French refers to Charles’ kinship with the French royal dynasty through his mother, Henriette Marie, a sister of King Louis XIII.

– A. Mo.

After Charles II’s return from exile, an elaborate coronation ceremony, which was carefully organised, took place on 23 April 1661. The portrait shows the king, who is depicted in Parliament robes over the costume of the Order of the Garter, sitting on the throne. His head is adorned with the Crown of State.

After the execution of Charles I, Parliament sold the royal crown, so a new crown was had to be made for Charles II that was identical to the previous one. The Orb and Sceptre were also recreated for the coronation. John Michael Wright has depicted the coronation regalia very precisely in the portrait. Charles II also wears the Sword of State and the Garter Collar with the Great George. The symmetrical structure of the portrait recalls depictions of earlier English monarchs and is intended to emphasise the continuity of the royal family.

One might assume that the painting was created shortly after the king’s coronation in 1661, but this is doubtful. The voluminous wigs came into fashion only in the 1670s and the jewelled buckles on his shoes were fashionable only beginning in 1666. It is not known on what occasion the picture was painted, where it was exhibited or whether it was commissioned by the king himself. It is possible that it was ordered by the goldsmith Robert Vyner, who had made the coronation regalia.

– A. Mo.

Catherine of Braganza was a Portuguese princess and daughter of King John IV of Portugal. Charles II married her in May 1662, primarily for economic reasons, as she was promised a large dowry. This unfinished portrait miniature was painted shortly after Catherine’s arrival in England. It depicts the queen, dressed in the English fashion of that time, which favoured much lower necklines compared to the Portuguese style.

Charles II preferred his mistresses to his wife from the very beginning. Catherine’s power at court was limited, as she failed to give birth to the desired heir. Moreover, as a Catholic, she belonged to a small religious minority. Nevertheless, from the late 1660s she began to promote Catholic Baroque culture, which increased her cultural influence. Thus, she patronised Italian Catholic painters such as Benedetto Gennari and Antonio Verrio, who soon took on a leading roles at court.

Catherine was also equally powerful in the field of music. She hired highly accomplished Italian musicians for her chapel, which therefore became a place where one could hear the best church music in the continental style. The queen thereby promoted Catholicism musically, and although she was of a different faith and did not provide an heir, she was able to gain recognition at court.

– A. Mo.

As a maritime power, England was almost inevitably in a competitive relationship with the Netherlands. The first Anglo-Dutch Naval War took place between 1652 and 1654 during the period of the Commonwealth. In 1660 the Netherlands made an attempt to improve the relationship between the two nations by offering a generous gift on the occasion of the accession of Charles II – but it was in vain. The conflicts continued during the reign of Charles II and led to two more wars in 1665–1667 and 1672–1674. The supreme command was in the hands of James, the king’s younger brother. Charles II himself appointed James the head of the British forces.

“Hell is empty and all the devils are here”

(William Shakespeare, The Tempest, Act 1, Scene 2)

In 1675 after the end of the third Anglo-Dutch Naval War, James commissioned two Dutch marine painters (Willem van de Velde the Elder and the Younger) to depict twelve important episodes of these wars. The painting shown here is by Willem van der Velde the Younger and is dated to 1676. It shows an event that is known as ‘Holmes’ Bonfire’. Under the command of Sir Robert Holmes, the British attacked a fleet of about 170 Dutch merchant ships near the West Frisian islands of Vlieland and Terschelling. Around 100 ships went down in flames. Although this event took place on two consecutive days, the painter combined both events in one picture. Winners write and manipulate history. Notably, the client used an artist who himself belonged to the defeated nation.

– K. He.

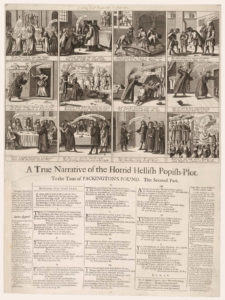

Conspiracy theories did not originate in the twenty-first century. Titus Oates, an outcast of church and society, already used the technique of lying to gain prestige and influence. The pre-existing religious conflicts between Protestants and Catholics made it easier for him to make his conspiracy theories heard. By maintaining that a Catholic plot (‘Popish plot’) to assassinate the king and re-establish Catholicism in England was afoot, Oates gained access to Charles II and was allowed to move into chambers in the royal palace. Yet he was soon to fall prey to his own web of deceit and would have to face the consequences of his lies. Charles II unmasked and condemned the slanderer, who had even accused the queen of being part of the conspiracy.

The engraving shown here mainly deals satirically with the ‘Popish plot’ in order to clarify the situation. The biblical comparisons used here, such as that between Oates and Judas, are meant to help establish the facts. Eventually Titus Oates ended up as he had begun, an outcast.

– K. He.

Thou shalt have no other Gods before me

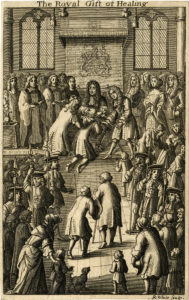

Many monarchs of the early modern period felt empowered by their supposed divine grace to heal subjects by laying on hands. Charles II continued the tradition of his predecessors by practising the so-called ‘touching for the king’s evil’. The term ‘king’s evil’ was used to refer to skin tuberculosis. Through the monarch’s touch, as through God’s hand, the afflicted would be healed and the veneration of the king would be strengthened. Charles II presented himself as a British saviour, and by doing so he emphasized his divinely ordained power. A ‘Touch Piece’ usually a gold coin used in the ceremony, strengthened the incentive for the sick to participate in the ritual, as they were permitted to keep the coin afterwards.

This engraving depicts Charles receiving the sick in the presence of members of the clergy and courtiers. A person seeking to be healed is kneeling in front of him. The king forms the centre of the composition, and his position is highlighted by a canopy. The numerous armed guards emphasize the power of the ruler. This depiction reflects the self-image of the king.

– K. He.

On the night of 2 February 1685, the previously healthy king suffered a stroke at fifty-four years old. Reports suggest that Charles uttered a horrible scream before collapsing. He was treated for four days by doctors using the methods of the time. While he was still conscious, Charles called his brother James and a Catholic priest to his bedside. On his deathbed, the former Anglican king converted to Catholicism. The priest performed the last rite, a Roman Catholic sacrament.

“We are time’s subjects, and time bids be gone”

(William Shakespeare, Henry IV, Act 1, Scene 3)

The following morning on the 6 of February, Charles II died.

This death mask shows the king’s appearance shortly after his passing. Charles II was buried without public viewing in London’s Westminster Abbey, the same place where his predecessors were entombed. His grave bore no name for over 200 years. He nevertheless remained in the memory of the people as ‘merry King Charles’, the incarnation of joie de vivre, and the one who had brought a lavish Baroque lifestyle to England for a short time.

– F. vdDi.

Because the marriage of Charles II and Catherine of Braganza did not produce any children, the question of succession arose long before Charles’ death. It became apparent that his younger brother James, the Duke of York, would ascend the throne. James had earned military honors as Lord High Admiral (cf. cat. no. 1.7.) but had converted to Catholicism, which alienated many contemporaries. The Popish Plot was an attempt to discredit Catholics and to exclude James from the succession. The Protestant alternative was an illegitimate son of the king, James Scott, 1st Duke of Monmouth. However, Charles himself supported his brother’s claims, and the younger Stewart succeeded as James II in 1685.

James’ policy didn’t go down well with the Protestant or Anglican population. Among other things, James was keen to strengthen the freedoms of Catholics and promote their influence. The final straw was the birth of an heir to the throne. After James’ Catholic wife Mary of Modena had long remained childless, she gave birth to a male heir on 10 June 1688, James Francis Edward Stuart. Therefore, the Protestants feared that in the future England would be permanently ruled by Catholics.

Seven high-ranking English Protestants then called on William of Orange to intervene. William invaded England with his troops in November 1688. After the invasion, James II fled to France, but in the years that followed, he repeatedly sought to regain his throne.

– F. vdDi.

William of Orange (later William III) presents himself here on horseback against the backdrop of the Atlantic Ocean, which is teeming with ships. On 5 November 1688, he landed with his troops on the Bay of Torbay, in the Southwest of England. Officially, he only wanted to help the British free themselves from the ‘tyrannical’ rule of James II, but he was also pursuing concrete interests of his own. William, who had grown up in the Netherlands, was a grandson of the English king Charles I and was also married to Mary, the eldest daughter of James II. Therefore, both Mary and William had a claim to the English throne, and as Protestants, they were, in the view of many Britons, better suited to govern the country than the Catholic monarch.

On 11 April 1689, William III and Mary II were crowned together. For the first and so far, the only time in British history, a man and a woman collectively assumed the highest power in the state. Although Mary had a greater claim to the throne than William, she refrained from an active political role. Only in William’s absence did she occasionally take over the affairs of the government. At their coronation, the pair took an oath that they would rule ‘according to the statutes passed by Parliament’. No English king had ever before accepted such a restriction of his powers by Parliament. England was henceforth a constitutional monarchy.

The lack of legitimate descendants of Charles II and the disputes over the succession ultimately led to a momentous upheaval in England’s history. In retrospect, these events were celebrated, as the Glorious Revolution, which had taken place almost without bloodshed. However, William III had to continually wage wars in order to, on the one hand bring Scotland and Ireland under his control, and on the other hand finally defeat the last supporters of the exiled James II.

– F. vdDi.